Pixar’s newest animated feature film, Toy Story 4, contains many challenging sequences where effects animation, simulations and procedurally generated effects were necessary to tell the new adventures of Buzz and Woody and the rest of the film’s characters.

Many of those sequences were made possible via the further adoption of Houdini at Pixar. A crucial rainstorm rescue scene at the start of the movie was a major Houdini sequence, while the tool also found use in scenes involving vegetation, cobwebs, dust and animated carnival lights. Pixar’s effects and simulation artists share their thoughts on where Houdini integrated into the pipeline.

The Houdini Pipeline at Pixar

In a number of recent Pixar films, heavy effects sequences have front-loaded the action, such as the video game in Toy Story 2, the playtime sequences in Toy Story 3, the ocean in Cars 2 and the Underminer in Incredibles 2. That tradition continues in Toy Story 4, as the car character RC is rescued by Woody and company during a rainstorm, with other sequences also drawing upon Houdini for various simulations.

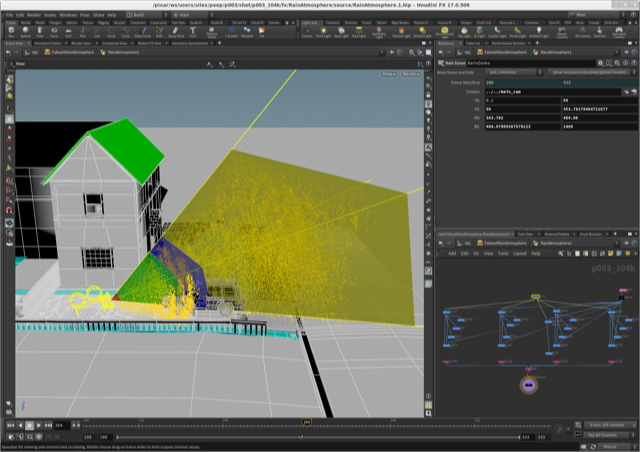

“Houdini 16.5 was the workhorse of Toy Story 4 effects for authoring all of our assets, although later during production a fresh build of 17.0 was made available to us by our tools team,” describes Pixar effects lead Alexis Angelidis. “We used Houdini to author all geometry types, shading signals and sometimes lights and shaders. Typically, we write all our assets to disk, before rendering them with RenderMan in Katana. We have to strike a balance between working as early as possible - to be part of a holistic vision of evolving shots - while minimizing the burden of continuously synchronizing files to remain up to date.”

“For Toy Story 4 however, our effects software engineer Michael Rice had developed two new workflows just in time for the show: Multishot, and a Houdini Engine RenderMan procedural. Multishot allowed users to manipulate a highly customizable network in a single interactive timeline for multiple shots. The RenderMan procedural workflow created a new place for early effects work at a very large scale. The latter turned out to be a perfect fit for deploying elements of the rainstorm rescue sequence.”

Angelidis notes that, in general, render time proceduralism is really incompatible with heavy simulations, as Pixar cannot afford to have the last frame hold the pipeline. To solve this in certain situations though, the team ‘deconstructed’ Houdini’s particle solver.

“A typical particle simulation uses two loops, to iterate first in time, and then on particles. Because all particles aren’t always visible at every time, reverting the order of these loops can be an improvement. And by solving the differential equation of motion analytically, we were able to get rid of the time loop. As an example, Michael O’Brien developed Duke Kaboom’s motorcycle sparks using the classic pipeline, and its conversion to a Houdini Engine asset enabled us to install our asset while animation was still working.”

Into the rainstorm rescue

Water and rain, of course, were the natural phenomena that Pixar had to simulate for the opening rescue scene. What was especially tough about that work was the wide range of scale required - from toy close-ups, to establishing shots of a ‘human’ neighbourhood. “It meant that our rain environment needed to be detailed under close scrutiny and modifiable in broad strokes," says Angelidis. “So we worked from the ground up, passing over the small scale detail to the larger scales. Geometry instancing was essential, and our effects software engineer Max Gilbert supported this pipeline, seamlessly connecting instancing from Houdini to USD.”

So much of the rain needed to be seen hitting the set, the actors and the toys, and to interact with it as it became puddles and splashes and rivulets. Since that would be an almost unachievable whole-scale rain simulation, Pixar chose to focus on very specific parts of the sequence, as Angelidis details:

“As we projected the rescue sequence work under the guidance of Gary Bruins, Eric Rosales and Alyssa Mar, it was very clear early on that our opening sequence would have to choreograph many custom elements generated by simulations and procedurals. We had to pick for early development the elements that were both in the most shots and the most likely to remain - and keep for later battles the elements that were more unique and could withstand a diversity of approaches.”

The team used the Houdini Engine RenderMan procedural workflow for modeling the falling rain in the atmosphere and the ground, and for the rivulets on the windows and the cars. “This let us modify all 100 shots with a small number of files, in the span of just a few minutes,” explains Angelidis. “That also meant we could do very minute changes on a large scale that would have been not worth doing in a more classic workflow.”

“The other advantage of this procedural approach was to provide to all artists an early context of falling rain to begin layering all the other rain elements. We were able to connect each rain drop with the fog, ripples, splash and spray, as well as obtaining natural dynamic rain occlusion. Our technical experts James Jackson, Brett Levin and Bill Reeves kept their fingers on the CPU pulse, and contributed to optimizations that pushed this large number of shots across the finish line.”

Many types of water

Since there were several ‘kinds’ of water and rain needed for the rescue sequence, Pixar split the work into teams of artists who had full creative control on choosing an approach to take. Each team used Houdini’s Flip simulation tool in some form, from the splashes on the characters to the drain and to the splashes on the ground. “Effects artist Greg Gladstone was at the forefront of using Houdini’s water simulation technology for the drain in the rescue sequence, while effects artist Amit Baadkar was pushing proceduralism in ways we hadn’t done before, and Matt Wong was propagating the falling rain in the sequence,” outlines Angelidis.

To achieve the splashes on the ground, the team relied on Houdini Engine to populate the world with pre-simulated clips of rain obtained with an array of Flip simulations. Says Angelidis: “The dynamics of Houdini are so customizable that Greg was able to combine the procedural atmospherical rain in the simulated drain water by injecting the splashes of the deterministic rain into the drain’s fluid simulation.”

Then, of course, each type of water and rain had to interact with something. To enable that to occur convincingly, most of the rain assets were done as geometry, with the exception of ground ripples, thin mud layers, wet cloth and roof shingles.

This explicit geometric representation of water gave direct control, bypassed the need to visualize shading signals when developing the look, and withstood close-up inspection. We also simulated vegetation assets for rainy weather, and moved the leaves for rainy weather conditions, so they would appear to be hit by rain drops. Houdini’s proceduralism is perfect for reconstructing phenomenologically water behavior based on reference footage, and Amit’s work on the windows in a great evidence of that.

Alexis Angelidis | Pixar Effects Lead

Meanwhile, water that interacted with characters was done as hero simulations. “Splashes were carefully placed and synchronized with animation, with Kylie Wisjmuller joining forces with Amit Baadkar,” says Angelidis. “Hiroaki Narita simulated drips for a character that walked undercover, and Krzysztof Rost added wetness on a large number of characters. Our team developed an expertise in rain by showering merchandise from past Toy Story movies to examine its behaviour in a Flip simulation.”

“A significant part of the success of this environment came from a close collaboration with lighting,” continues Angelidis. “Rain covers such a wide area in the frustum, that it's like a canvas of potential visual energy that can be revealed by lighting. Jesse Hollander, Lloyd Bernberg and Amy Jones figured out the rules of the environment for locking the levels of raininess.”

In terms of the workflow for the sequence, one driving factor in how the data was pushed around and how rendering occurred came from the fact that rain is such a reflective surface that, according to Angelidis, the team “needed the full context of the shot to make informed decisions.”

Houdini combined with USD is a very versatile tool for connecting all the pieces of a pipeline. Houdini provides alternatives for importing USD from Presto [Pixar’s proprietary animation tool], and likewise for exporting USD to Katana and RenderMan, with the USD python bindings as a safety net. Also our RenderMan team provided us with a great all-purpose renderer that supports all types of geometry as first class citizens: surfaces, points, instances, curves, volumes. This also includes thin volumes, which have been a long standing productivity obstacle.

Alexis Angelidis | Pixar Effects LeadHoudini Helps Tell the Story

While the rainstorm rescue was the front and center Houdini sequence in the film, there were numerous other scenes and assets where the tool helped to make a difference. For example, the Toy Story 4 simulation department had been looking at ways to optimize generally for the upcoming production. One area they knew needed improvement was their hero vegetation pipeline.

“Characters interacting with vegetation has always been a problem area for the department,” admits simulation technical artist Matthew Benson. “It took a long time and was difficult to iterate on. So, when Vellum came out it seemed like such a clear solution to what had long been a thorn in the department's side. The new pipeline bakes down the procedural vegetation into USD files, imports them in Houdini, and runs them through Vellum, and exports them back out as an animation point overlay USD file. The whole process is now much cleaner and much easier for artists to use. Our turnaround time went way down, and our fidelity of interaction way up.”

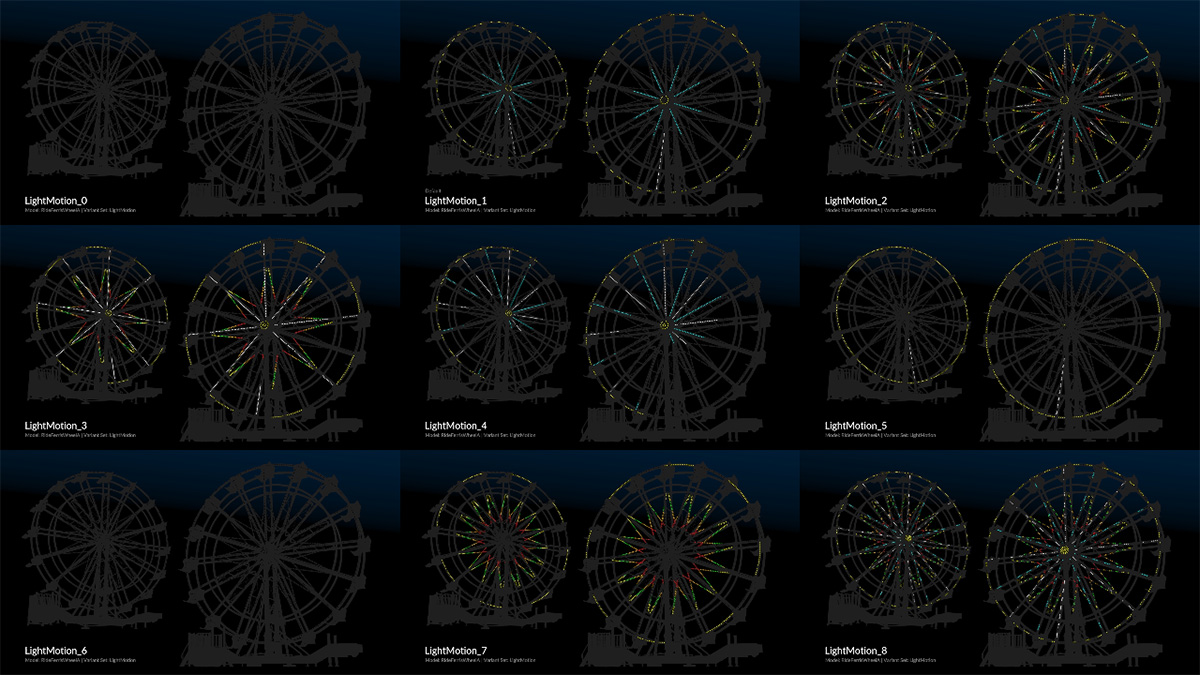

In the film, the characters visit a carnival site, in which hundreds of neon and other lights needed to be ‘animated.’ Houdini was used here to animate the carnival lights, operating on point instancers of light bulbs read in from cached USD files of carnival rides and booths. “Expressions using geometric parameterizations and spatial attribute transfers from simple geometry in motion provided a basis for on and off bulb states,” says sets technical and extension lead David Luoh. “Variation and decay imitating real world physics were additionally introduced with proceduralism and simulation.”

Then there was the vast and dusty environment of the antiques store. Here the set extensions team developed a Houdini process to generate dimensional, granular elements such as dust and small debris. “Houdini was integral in generating initial distribution, simulating a history of character interaction, and facilitating flexible artist workflows,” notes Luoh. “A Houdini Engine render-time procedural was also used for dust as a strategic optimization.”

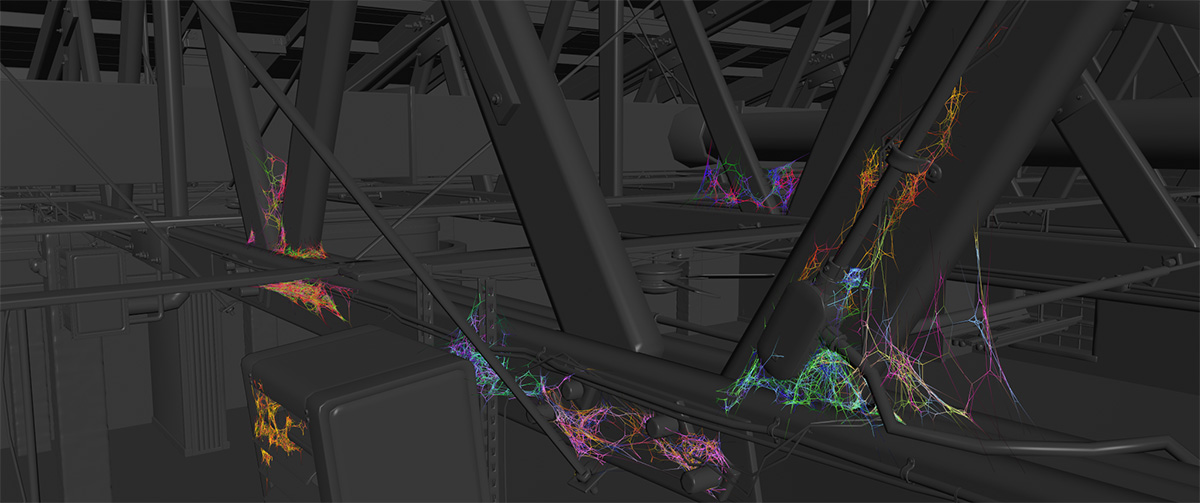

Adding to the ambiance of the antiques store scenes was the presence of many cobwebs, which were generated using a simulator in Houdini. This imitated spider behavior to build complex cobweb structures. “Artists designated areas for cobwebs and scatter initial lines from which digital spiders would jump, altering existing structures and generating new web lines,” describes Luoh. “A smoothing filter was applied to mimic tension, and in some situations constrained simulations were run to introduce additional physicality.”

COMMENTS

weizhongyuan 4 years, 8 months ago |

希望houdini能有中文版,中国有13亿人的市场。中国的科技公司现在都在飞速的发展,动画,影视也都是在迅速的发展。中国市场前景广阔。

rexpanyue 4 years, 8 months ago |

版权是个大问题啊。亲。。哎

ZebangZhang 4 years, 7 months ago |

mo mo da

David Inlines 1 year, 4 months ago |

Awesome article!

Please log in to leave a comment.